By Emily Blobaum, Fearless editor

All of the major LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations and nonprofits in the Des Moines metro are being led by women or nonbinary people, many of them having programming with a statewide reach. In two separate group interviews, I met with six LGBTQ+ leaders and talked about why this is significant, the importance of intersectionality and visibility in leadership positions, and how they lead their organizations.

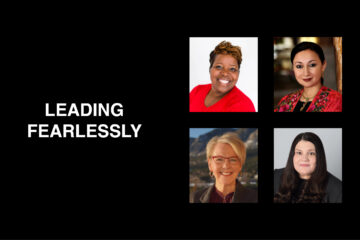

- Jen Carruthers (she/her), president of Capital City Pride.

- Erika Hendel (she/they), co-chair of the Iowa Queer Communities of Color Coalition and board member of the Des Moines Pride Center. They also work as a veterinarian.

- Buffy Jamison (they/them), co-chair and co-founder of the Iowa Queer Communities of Color Coalition. They also sit on the boards of the Iowa Coalition for Collective Change and the Central Iowa Center for Independent Living.

- Diana Prince (she/her), president of the Des Moines Pride Center. She also manages two Bank of the West branches.

- Courtney Reyes (she/her), executive director of One Iowa.

- Becky Ritland (she/her), executive director of Iowa Safe Schools.

While these interviews were conducted in group settings on Zoom, the views of one person do not necessarily reflect the views of the others. These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

All of the major LGBTQ+ nonprofits and organizations here in the Des Moines metro are being led by women or nonbinary folks for the first time. Why is this significant?

Jen: It’s significant because it’s never happened. What it really comes down to is diverse perspectives. I hate the phrase “the table,” but we are still very much in a culture and society where the table is where the decisions are made. And when you don’t have the perspectives of women or women in the queer community or a person of color in the queer community, the events or initiatives that we put on tend to look like how the leadership looks. I would love the table to go away at some point, but that’s not a reality right now. I feel like we’re breathing fresh air into these organizations that haven’t had it before. With Capital City Pride specifically, we went from an almost all white male cisgender board to the most diverse board we’ve seen in 43 years. That’s not because we tokenize anyone, it’s because people are starting to see the change in leadership and so naturally want to become more involved.

Courtney: I love the idea that there won’t be so much gatekeeping to get into the room. But we are a long ways off from that. But that’s why we keep interrupting the cycles. When you think about why it’s important to have leaders that aren’t white cis men, I think back to one of my first meetings as executive director and I showed up to the meeting and every single person was a white cis gay man. I don’t want to ever seem like I’m bashing men, but I do think that queer women and femme and nonbinary folks bring a different perspective because we’ve had different life experiences. A lot of value comes from having different perspectives at the table. There’s something empowering about there being other femme people leading an organization.

Becky: It symbolizes that we’re really starting to move on from the marriage equality narrative. Marriage equality for a long time has been front and center of the LGBTQ movement, especially here in Iowa. And it’s amazing, many individuals have benefitted from that. But the marriage narrative has also left a lot of folks behind, specifically youth and trans and nonbinary folks. … So to see that the queer organizations here in the state of Iowa are seeing a shift in leadership, I think that it’s also bringing a shift in the narrative that there is still a ton of work to do. We still have a lot of folks who don’t feel safe and don’t feel that they’re being equally represented or having their voices heard.

Erika: I think one thing that is reflective and similar to what Becky was saying is about intersectionality and diversity. Visibility is really important. I’m Asian American. I’ve lived in Iowa for 4½ years, but it was a difficult transition coming from some of the other diverse places that I’ve lived. I found the most sense of community with the diversity that I experience in the queer organizations in the city. I think the lived experience that the leadership has is unique. Intersectionality is important for the well-being of our community.

Why is visibility and intersectionality in leadership positions important?

Courtney: We all bring different things from our life experiences. I’m newly out, but I think that’s one of my intersections that helps me challenge things because I’m like, “I’m new here. Let me ask some questions.” That’s actually one of the reasons I took this executive director job, because I did not see many parents in leadership positions, specifically mothers. I had one person who I saw that in, and that’s Jenny Smith ― she’s one of my mentors. She had a successful business and a family, and I thought that was really important, to be able to make sure other people could see it. And Sonia Reyes, one of my other mentors, is a mom and a Latina. When I became the executive director, everyone was like, “Oh, my gosh, it’s so great to have a person of color running One Iowa.” Never in my life had I identified as a person of color. My grandfather came from Mexico, I’m half Mexican, but I’m very white-passing. That was something that I hadn’t put a lot of thought into, and then everyone put that label on me. It felt really strange and I didn’t like it because I didn’t ever want to take anything away from other people of color. Then I had a conversation with Sonia and she said, “You have no idea how many times you’ve been discriminated against, didn’t get an opportunity or a meeting because your last name is Reyes. You don’t know how many brown kids, brown queer girls, see that you are leading this statewide organization and how much of an impact you can have on them even if they never meet you.” I took that pretty seriously. This is why we have to have an intersection of folks leading organizations. It’s so good to be able to see yourself in a leader.

Jen: What I’ve been trying to change the narrative on is the term “ally.” I’m sick of that term because it’s passive. I’m trying to get to a point of “accomplices,” where people are actively participating to change the narrative and using their position of privilege to do so. I think this goes into representation discussion because it’s changing the narrative of presence versus representation. There can be a presence of intersectionality in our community, but until there’s actual full, active representation in these different leadership positions, the narrative doesn’t change. [Queer women] have always had a presence, but there’s never been an opportunity. That’s the big difference. And I think women are really starting to seize the opportunity.

Courtney: To piggyback off of that, I think it’s one thing to have women in positions of power, but for those women, specifically white cis women, I think it’s on us to continue to give up our power and privilege to make room for folks who have less power than us right now.

Diana: Visibility is important because the world is changing. One of the bank branches that I manage is in West Des Moines. At first, people are surprised that a Black person is managing a bank out here. But then they’re excited that in the state of Iowa, there is representation. And that there’s representation not just in entertainment. Black people can manage businesses and organizations and do it successfully.

Becky: At Iowa Safe Schools, we work primarily with students ages 11 to 24. In studies, what we find is that when a queer student can see themselves in a leadership role or they can identify some part of themselves with a leader in their community or in a career that they’re interested in pursuing, they do better in school, they’re absent less often, they experience bullying and harassment at lower rates, and their mental and physical health is better attended to. So from the student perspective, representation is important because it shows individuals that you can truly pursue whatever you want to pursue. Historically, students have thought that in order for them to be out and in a position of leadership or work in a STEM or finance field, that they need to go to the coasts where it’s more progressive. So as we’re seeing more diverse leadership coming into power here, as women, as queer individuals, as nonbinary and trans folks, we’re taking the leadership baton and saying that we’re going to run with this. [By doing that we’re also] encouraging students to stay in Iowa and help them recognize that there’s a place for them here.

Buffy: It’s important to understand that all oppression is connected and multiple structures and systems of oppression work together to harm. If we’re not keeping that in mind, we’re going to leave members of our community behind, and those members are usually the ones who are most marginalized. We have to get to the root of the problem instead of just applying Band-Aids.

Erika: I think one thing that’s really important within intersectionality is that there’s also a lot of collective and intergenerational trauma. For me personally, mentorship has been something that’s been particularly profound in the last couple of years. I have a Ph.D., I have a veterinary degree. I’ve spent my life in STEM and no one that I was receiving mentorship from looked like me or understood my lived experience. So that’s why intersectionality and leadership is important, because those are people who are also mentors and are influential in whether or not the next generation is uplifted or pushed down. A lot of times, when intersectional and marginalized individuals finally get up into leadership positions, they’ve done so off of emotional and physical fumes. And sometimes, when you’re in those positions and if it’s isolating, it can be incredibly difficult to continue. Mentorship, support and creating empathetic spaces for people who have experienced multiple levels of trauma is important. This type of leadership where the leader is strong all the time … it’s not that easy. That’s not the same way that leadership works for marginalized people. So that’s one thing that I worry about as far as intersectionality in leadership goes. How do we keep those diverse individuals that are taking leadership positions and training the next generation? … How do we create a system of support?

Buffy: In our society, the way we are taught about what heroism is, what it means to be a real leader, it usually comes with some level of sacrifice, right? We have to really interrogate these parts of our society and really think about why it’s this way. So when it comes to leadership, people just need to step up more. So many people think you have to be XYZ to be a leader, but you don’t.

So if you had to put it into words, what are your leadership styles?

Jen: If I had to explain it, I think I lead very fiercely with a lot of passion. I lead with my heart more than anything else. That’s why I give as many hours as I do to this community. I think the main piece in my leadership style is that I don’t ever ask anything of anyone that I would not personally ever do to myself. Especially in positions of power, you feel that you can just delegate all of the time and that you don’t have to do as much work sometimes, right? That is definitely not me. I’m usually the one leaving the office last. And it’s not because I’m trying to prove a point, it’s because I’m trying to get things done.

Courtney: I have an authentic leadership style, heart-led. But as I’ve explored that more, what’s been really important to me as a leader is empowering the folks around me. I’m not an expert trainer. I could come and give a presentation, but Max [Mowitz] or Keenan [Crow] can do that much better. So I believe in building a team that really complements each other and values folks. Not only are we trying to do this work that can be very trying – like, for example, the 15 anti-LGTBQ bills – those bills are targeting us as human beings. So a lot of times I can show up as Courtney, the executive director of One Iowa, and be pissed about it and get something done. But then there’s times where it’s like, no, this is me as a human, and you’re trying to make it so my family can’t live here. So I try to find that balance in my leadership of really trying to touch base and build that trust and empower my team to take care of themselves. I value the humans that are working for me. So I’m different than you in that way, Jen, because I really encourage my team to work 32 hours a week, not 40, because we are doing this heart work that’s hard on our bodies.

Jen: I will clarify, I don’t ask anyone to work as many hours as me. There’s no question when I do ask people to do something, that I haven’t already done that. I’m a workaholic. And I don’t have a partner or kids. I have a dog. So it’s really easy to make this work, because it doesn’t feel like work. I definitely don’t try to be a transactional leader. We’re not paid, so the only thing that I can do for my people on my board is check in and see what they need from me and make sure that they feel valued.

Becky: From my perspective, it’s kind of a two-pronged approach. I try to have extreme transparency and extreme collaboration. … I think the only way that we can really accomplish things as leaders is to be as collaborative as possible, and not come at it from an authoritative [approach]. The other prong is a level of extreme ownership. We have to make sure that we’re giving credit where credit is due and if something doesn’t go according to plan, you take a step back and say, let’s regroup, let’s reengage, let’s figure out a way to move forward without necessarily pointing blame at a certain individual or entity. So how I approach leadership is, how can I make sure that I am being of service to the group of individuals that I’m leading, so that they can be of service to the community members that we’re serving?

Buffy: My leadership style is anti-hierarchical. I hate hierarchies. I very much like when we are all working on something together and everyone has a say. I want for folks to walk into this space and take over. … People really need the opportunity to have practice to assert themselves. Not just for the sake of leadership or the sake of being able to produce something for society, but for the sake of being able to assert yourself and recognize that your voice is powerful.

Erika: I’m definitely more of the collaborative collectivism. I think that’s what I observe to be most common in organizations that are trying to shift change. I would say my leadership style leads toward facilitation and understanding of how to get the most positive experiences for everyone.

Diana: A servant-oriented leadership style is something that I’ve always grown up with. I’m one that’s here to serve others. However, because I also work in corporate America, I have to adhere to hierarchical-type situations and make decisions. So sometimes those two styles butt heads.

So to wrap things up, what are your goals for the future within the LGBTQ movement and/or community here in Iowa?

Erika: I’ve been trying to communicate to a lot of the really great people who are showing up and expressing great allyship that there’s a distinction between educating yourself to be more aware and actionable outputs. What I’m focusing on right now is continuing to bring attention and awareness back to the questions of what’s important to them and what they’re struggling with, but also knowing that they might not be willing to share that quite yet. Trust is something that’s built, and that’s hard for a lot of people who are showing up and have genuine intentions. … I saw an article recently that said instead of calling it diversity, equity and inclusion, it’s belonging, dignity and justice. I just want people to treat others with empathy and kindness. Just don’t be a jerk.

Becky: From my own journey toward equity and inclusion and creating that sense of belonging, part of it is moving away from the idea that cultural competence is the goal and that we really need to be moving toward a journey of cultural humility. So moving away from the idea that I can have a working knowledge of communities of color, trans and nonbinary communities, rural individuals … whatever the population is, and moving toward the notion that I need to go out and engage with these community members. You may have that working knowledge, but at the end of the day, you need to be hearing it directly from community members as to what I can do to help lift up voices and create opportunities for people to step into their power and into areas of leadership. So as Erika was saying, I might approach someone and ask what they’re struggling with, and they might say that they’re not quite ready to have that conversation yet and that there needs to be real change before we can move forward. Part of cultural humility is understanding that and accepting that answer but continuing to rebuild trust in communities and show through actions, not just through performative conversations. It’s not just enough to invite people to dinner and have a place for them at the table. We also need to have things at that table that represent their needs. We need to have food that they want to eat. And we need to step back and say that we’re not the expert and ask how we can do better and what we can do to move forward in a way that is creating spaces for all individuals to step into areas of leadership.

Diana: We have to widen the tent and give people space, an opportunity to feel empowered and share their opinion, or at least give them a space to have a voice. … I think about the trans community and how it’s the community that’s most frequently attacked. When it comes to people who need wins, I’m giving people the opportunity to be able to have that power and let them know that they can be successful. I read a study a couple of years ago that said 56% of people in the trans community have a bachelor’s degree or higher. But yet, when it comes to roles like mine or opportunities for advancement, there’s next to nothing. So where does that come from? How do we get past the issue of “marriage equality is a thing, so now we’re good?” How do we lift every voice regardless of their intersectionality?

Buffy: People really need to start understanding intersectionality – and quickly. If we don’t figure this out soon, things are going to be bad. Intersectionality is more than identities or how many people in groups are diverse. It’s about systems, it’s about structures. And then in the short term, we have to move away from tokenism.

Jen: I want to leave behind a more diverse group than what I received. I want to put in the work of ensuring that this isn’t a fluke that these women are in these positions and we just revert back to the old way.

Courtney: As a part of my job, I have to talk to a lot of people who are in positions of power and very rarely are those people queer people, women or people of color. I want there to be more LGBTQ leaders. I want LGBTQ people on the soil and conservation board. I want LGBTQ people on the Broadlawns board. I want them everywhere. I want to have a Rolodex of queer folks that people can go to. [As far as what Becky mentioned in terms of moving on from marriage equality], we have much farther to go. Marriage was just the tipping point and a cultural shift. Queer, cis folks are the ones who need to be doing the work so we can make space for our trans and nonbinary friends and siblings. The 15 anti-LGBTQ bills, 10 of them were targeted directly at the trans community. So that’s where the work lies. That’s where being an accomplice lies. I’m in the queer community and I still need to be an accomplice. I have more power and privilege and I really need to get to work. Obviously, I’m biased to our mission, but people need access to health care. I need to be able to show up to the doctor and not be discriminated against because I’m queer.

Jen: It’s the same thing for me. The T in LGBTQ and the nonbinary part of our spectrum is being left behind. We have gained a lot more rights. I look at the difference of when I came out 20 years ago and I do have a lot more privilege as a gay person. It’s one thing to see anti-LGBTQ bills, but when you take out and only pinpoint that one letter, it’s a whole new level.