As she neared graduation, University of Utah track athlete Lauren McCluskey embraced her future. She felt "on the verge of something new."

Then came a new love interest, and a string of lies, emotional abuse and terror.

As the danger mounted, Lauren sought help. It never came.

LISTEN

A story about what happens when the people and institutions that are supposed to protect, fail.

By T.J. Quinn and Nicole Noren

Lauren McCluskey flew home that weekend with doubts. She had been dating someone for a month, and it had gotten serious fairly quickly. Sean Fields was a good bit older -- 28 to her 21 -- with some old-fashioned romance about him, buying her flowers, taking her to nice restaurants. She was a senior at the University of Utah and generally had been too busy with track and school to date much.

But just before she headed home to Pullman, Washington, for fall break that first weekend of October 2018, she saw his state ID card and the name of a different man, Melvin Shawn Rowland, 37. He quickly explained that it wasn't what she thought, that he had fake identities for numerous reasons. She accepted his explanation in the moment; if anything is clear about Rowland's life, it's that he could be persuasive.

At home during the break, Lauren met her best friend from high school, Regina Snider, at a favorite gastropub, Birch & Barley. Lauren had been doing some research and told Snider there was something strange about her boyfriend. For an hour in the nearly empty restaurant, they sat in a corner booth and scrolled through Lauren's phone, searching for answers. Sean Fields had little social media presence. But the name Melvin Shawn Rowland did pop up -- under police mug shots. This man was a convicted sex offender. He looked like the man Lauren was dating, but even then, Snider says, Lauren wasn't sure. It didn't seem possible.

Snider took out her phone and snapped a picture of Lauren's screen. Just in case she had to show someone someday.

The day before Lauren left Pullman, she spoke to her boyfriend by phone and even had him say a quick "hi" to her parents. Lauren didn't tell them or let on about what she had learned. But she left home for the last time thinking she needed to confront Sean, or Shawn, or Melvin, or whoever he really was.

WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY

LISTEN, an ESPN original documentary on this investigation, will debut at 7 p.m. ET on Tuesday, March 28, on ESPN+ and ESPN+on Hulu. The investigation also will be the focus of a two-hour report, anchored by David Muir, on ABC's 20/20 at 9 p.m. ET on Friday, March 31.

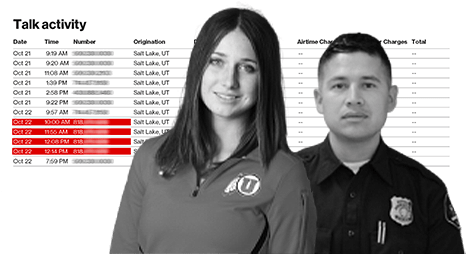

Interviews and records obtained by ESPN show a campus system, led by then-University of Utah President Ruth Watkins (left), that failed to respond after Lauren reached out for guidance and protection.

A SERIES OF FAILURES

The first thing most of the world knew about Lauren McCluskey was that she was a Utah track and field athlete who had been killed on campus. Her Oct. 22, 2018, shooting death became national news.

The first thing anyone knew about Melvin Shawn Rowland was that he was a killer, and that he, too, was dead. Stories about Lauren's slaying didn't provide many details about Rowland -- only that he had spent years in prison before he entered, and then ended, Lauren's life.

But a closer look at the paths that led to Rowland killing Lauren show an agonizing series of institutional and individual failures. ESPN spent more than four years interviewing Lauren's family, friends, and state and local officials, and reviewing thousands of pages of documents and hours of video and audio obtained through open records laws. For weeks before her death, Lauren and her friends repeatedly raised alarms about Rowland with University of Utah campus police and housing departments. Even Rowland's co-workers and employer had opportunities to intervene but did not, according to police interviews and documents.

The most glaring failures were by campus police. According to state and university investigations, key police personnel were inexperienced and inadequately trained, senior officers did not track Lauren's case, information wasn't communicated between shifts, and the chief had an unwritten policy of limiting the department's contact with Utah's Adult Probation and Parole office.

Then, after the killing, the university repeatedly botched its response. It took two years for the school to apologize to Lauren's family and acknowledge mistakes.

Interviews and records obtained by ESPN show that Lauren repeatedly reached out to officials, putting herself in the hands of a system that was supposed to protect and guide her through her own uncertainty.

There is no single moment when a different decision or action definitely would have saved Lauren's life. But the right decision at any of several points might have.

too good to be true

Jill and Matt McCluskey picked the name Lauren for their first child because it sounded pretty and strong.

Lauren was born in 1997 in Berkeley, California, where her parents were working on their doctorates at the University of California. The McCluskeys later had a son, Ryan. Jill is now a professor of agricultural economics at Washington State University in Pullman. Matt is a physics professor at the school.

By the time Lauren was 2, the paradox was obvious. The girl who was shy meeting people climbed trees as if gravity didn't apply. When Lauren was 8, Jill and Matt entered her in a Junior Olympics meet in Spokane. Lauren competed in the 400-meter run, the high jump and the long jump. She set regional records for each. She went to nationals when she was 10 and took fifth in the pentathlon.

In high school, Lauren finished 10th in the heptathlon at the USA Track and Field Outdoor Junior Championships. She won a state title in the high jump and was a good student, so she had her choice of colleges. She fell in love with Utah, tucked into the upper northeast of the Salt Lake Valley. For someone who grew up in Pullman, Salt Lake had the familiar comfort of nearby mountains but the feel of a larger city.

Lauren made a face when she competed, her friend Snider says. "It was, 'I'm gonna win that race no matter what.'" It was jarring if you knew her only as the friend who cared deeply about animals and sang karaoke. "You see her in track and field, and then you're like, 'That's Lauren? Like, that nice person?'"

Lauren even sang that way in her church choir, Jill says. "She would just sing the hymns at the top of her lungs."

When Lauren crossed campus with her red track and field backpack, she seemed almost grim, her sharp blue eyes cast down. But when you'd say "hi," those eyes met yours and she brightened, says her friend Alex, who asked that her last name not be used. Lauren was just intensely focused -- someone who was much better at listening than sharing. Lauren typically rose early. She'd attend a morning track workout, go to class, go back for an afternoon track practice and return to her dorm to study.

She'd had a serious boyfriend earlier in college but otherwise hadn't dated a lot. She also didn't discuss wanting a relationship. She talked more, Alex says, about what she wanted to do after graduation -- something with animals, or something in public relations or academic advising. The closer she came to graduation, the more Lauren started to open up her world, spending more energy on singing and comedy than the heptathlon. Her track career fell short of expectations, Jill says, mostly because there was so much more Lauren wanted to do, so many ways she wanted to grow.

In her journal in January 2018, Lauren described her ongoing evolution toward the person she was "meant to be."

"I keep feeling that I may be on the verge of something new; some sort of epiphany driven by catharsis," Lauren wrote. "Reflecting upon all my past choices, emotions, obsessions, and perceptions, it occurs to me that I am still alive. I have made it through all of it and have gained a stronger sense of consciousness.

"I will never be perfect, nor will I ever seem as good as those who seem perfect to me. But, perception of perfection is not a true reflection of how people truly exist. Flaws will continue in us so long as humans continue to breathe. I intend to embrace the hardships; the bumps in the road that I must stumble across to become who I am meant to be. I am ready."

Jill says she and Lauren spoke every day. "She was pretty open, but I know she didn't share everything."

Lauren met the man who called himself Sean Fields on Saturday, Sept. 1, 2018, when Lauren and Alex went to the London Belle, a bar in downtown Salt Lake City. Sean worked there as a bouncer. Alex remembers he was "huge," muscular -- built like a football player. The place was filling up but they found a table in the back. Sean stopped by several times to talk. Something was up with Lauren that night, Alex says. Whatever it was, she didn't seem like herself -- Lauren's shy intensity wasn't there.

Alex says she found Sean "abrasive." He kept looking at her like she was stupid. But she could understand why other people found him charming and why Lauren was attracted to him.

Around midnight, when Alex and Lauren were ready to leave, Lauren wrote her phone number on a napkin to give to Sean if they ran into each other. The place was so packed that Alex didn't think they would see him. They pushed through the crowd toward the door, Lauren leading, and there he was. Lauren gave him the napkin and ran ahead of Alex, as if half-panicked at her own boldness. "I think I said, 'I can't believe you actually did that,'" Alex says.

Sean started texting Lauren later that night. At church the next morning, Lauren told Alex that she and Sean were going on a date later that day. Alex thinks they went rock climbing.

Sean said he was 28, a part-time student at Salt Lake Community College studying computer engineering. He was bright and kind of a fitness nut, something that clicked immediately with Lauren. For someone his size, about 6-foot-3 and somewhere above 200 pounds, his soft voice was disarming.

He bought her flowers. Lauren gushed that no one had done that before. Snider, a time zone away in Pullman, heard only Lauren's take on the relationship. "You don't investigate something if that person says, 'I'm happy, I'm in a good place so far,'" she says. But, she says, "It sounded too good to be true."

Lauren's friends in Utah say they quickly noticed little things, like Sean telling Lauren what to wear and with whom she could spend time. The strangest thing, what seemed least like Lauren, was her sudden need to immediately answer every one of his texts and calls.

Alex was with her at Target once when he called. Lauren tried to answer but had bad reception. She rushed to find a good spot to call him back. Alex could hear his voice. He sounded "very mad," barking questions at Lauren: "Why didn't you answer? Where are you? Who are you with?"

Lauren explained to her friends that he'd been hurt by a previous girlfriend who cheated on him. That she needed to earn his trust.

Lauren's Google calendar entries for September make numerous references to him: "Pick up Sean @ 4:30." "Meet Sean at library." "Church w/ Sean (heart)." Over the next couple of weeks, Alex says Lauren started picking up Sean from work when he finished at 2 a.m. -- he said he didn't have a car but was saving for one. Lauren started napping during the day. She looked tired. He stayed with her in her Shoreline Ridge student apartment most nights and became enough of a fixture that other dorm residents recognized him and let him in the door.

Sean bought her pepper spray. Then he wanted to take her shooting. On her Google calendar, there is an entry on Sept. 23: "Shooting w/ Sean." It was weird, Alex says; Lauren always said she hated guns. "Before she went, she told me, 'He wants me to get a gun.'"

Alex says she told Lauren about her increasing concerns, that there was nothing normal about Sean's paranoia or desire to control her.

"She kept saying, 'We all have baggage, we all have baggage. It'll get better. Hopefully he'll start to trust me more. It'll get better.'"

‘THIS IS TOO MUCH’

By the end of September, after Lauren and Sean had been dating for a month, Alex reached out to other mutual friends. They shared the same concerns about Sean, and Alex says she thought, "OK, it's not just me."

On Sunday, Sept. 30, the same friends asked Diamond Jackson, who oversaw the resident assistants in Lauren's dorm, to meet.

The friends told Jackson that Lauren seemed different now. They thought Sean was too controlling. He was making her buy expensive items. He was keeping her from her friends, and he wanted her to get a gun. They also told Jackson they thought they saw bruises on her body and worried he might be abusing her. Alex says she saw bruises on Lauren's legs but thought they might be track injuries.

"I was like, 'This is too much,'" Jackson says. "This is beyond dating someone that's not fit for you. This is dating someone who is a danger to you."

Jackson says she first reached out to Emily Thompson, her residential hall director, on Oct. 2. Thompson had been in her job only a few months.

Jackson says Thompson told her to reach out to their supervisor, area coordinator Heather McCarthy. Thompson and McCarthy told Jackson to fill out an electronic report under the school's CARE system, which would place Lauren's situation on the agenda for an Oct. 8 CARE meeting, a regularly scheduled gathering of resident directors to discuss students who might need support.

But Jackson says the software was down and she couldn't file the report. Instead, she sent an email to McCarthy with her concerns. That Oct. 2 email, with the subject line "Student Concern," later obtained through a records request by ESPN, detailed Lauren's friends' concerns. Jackson wrote that Lauren "may be [in] a potentially harmful relationship," that she has said her boyfriend is getting her a gun, that Sean was "tracking" Lauren and that Lauren "is not taking care of herself." Jackson concluded the email by saying friends "want someone to reach out to Lauren."

Jackson says she never got an email response from McCarthy. The next day, Oct. 3, she attended a weekly meeting with the two supervisors, McCarthy and Thompson. (Neither responded to interview requests from ESPN.) Jackson says she asked what could be done about Lauren's situation. She says she was told that, for privacy reasons, not much could be done, and that she should simply keep an eye on Lauren.

Jackson says she approached Lauren one morning, "friend to friend," to raise her concerns. She says Lauren was too stressed about getting to class on time to talk. Jackson says she didn't follow up. "I didn't want to pry further," she says. "That is something I really regret."

The Oct. 8 CARE meeting never happened. "It wasn't rare for those meetings to be canceled," Jackson says.

The housing office also has a behavioral intervention team to evaluate cases where a student might need help. But a school investigation later determined that no one entered information about Lauren's situation into the team's database. And no one ever told police there might be a gun involved.

Jackson says there was an unwritten rule among housing staff that campus police should be called only as a last resort. "We did not have a good relationship with the cops," she says. "We didn't like them interacting with students, even when it was a point where they should be interacting with students."

In interviews with ESPN, two former campus police officers who spoke on condition of anonymity backed up Jackson's impression of strained relations between police and housing staff.

CALL FOR HELP

About the time Jackson was trying to raise alarms with housing superiors, Lauren went home to Pullman, where she did the internet sleuthing that determined her boyfriend was actually a 37-year-old sex offender.

By Oct. 9, Lauren had returned to campus and decided to break up with him.

She called Alex to talk through how she might do it. Alex advised Lauren to pick a public location. While they spoke on the phone, Rowland appeared at the window of Lauren's first-floor dorm room. Video surveillance footage shows him arriving at her building at 6:33 p.m., heading toward her window, then moving to the building's door 12 seconds later to wait. Lauren wrapped up her call with Alex. The video shows Lauren meeting him at the building's entrance and greeting him with a smile and a kiss. They hold hands for a second, and she leads him inside.

Alex spent the night worrying, not knowing what was happening in Lauren's dorm room. The next morning, at 11:49, Alex called, and Lauren said she couldn't talk. He was still there.

At 12:28 p.m., Lauren called back.

She said that they had broken up but that Rowland spent the night. She said that she had confronted Rowland about his identity and his criminal history and that he insisted the allegations that made him a sex offender were false. He told her that the victim was 17 and had lied about her age, that he had been set up. She finally told him she needed to go to track practice, but she let him borrow her green Jeep Liberty just to get him out of there.

So he was out of her room and hopefully out of her life. She just needed to figure out how to get the Jeep back.

A few hours later, she started getting text messages from unfamiliar numbers. They were purportedly from Rowland's friends, asking why she had broken up with "the big guy" and saying that he truly loved her. Alex says one of them read, "I thought you were supposed to be at practice," and Lauren didn't understand how one of Rowland's friends would know that. That message, and others filled with obvious grammatical and spelling mistakes, made Lauren think he was texting her himself, but she couldn't be sure. Finally, a text said that "Sean" didn't want to see her and that one of the friends would drop her Jeep at the stadium parking lot.

Lauren told her mom about the breakup and what she had discovered about Rowland. Jill says she felt sick to her stomach but didn't immediately worry because as far as she knew, "[Rowland] didn't give any indication that she was unsafe."

But he had Lauren's Jeep, and the more Jill thought about it 500 miles away in Pullman, the more worried she got.

At 3:01 p.m. on Oct. 10, University of Utah police received a call.

"I'd like to request some help for my daughter," Jill began.

She told the dispatcher that Lauren and Rowland had been dating, but "he was lying to her. He's actually a sexual offender." Lauren needed to get her Jeep back, and "I don't want her to go by herself and have something bad happen to her."

By the end of the call, Jill's voice was cracking with emotion. The dispatcher, a young woman, was reassuring, taking Jill seriously and working to find a solution. The dispatcher called Lauren to coordinate. She told Lauren she had been in a situation like that herself. The dispatcher offered to have an officer bring Lauren to the stadium parking lot and wait with her until she got the car back.

"If it's all right with you, we're here 24-7, I'm super cool, you could come here [to the police station] and have him drop it off here," the dispatcher told Lauren.

Jill says Lauren seemed reluctant to involve police. But Lauren agreed to let an officer bring her to the parking lot and watch her from a distance as she retrieved her car. The dispatcher called Jill to tell her the plan; Jill was pleased. "I feel like he has a little bit of control over her, that something bad could happen," Jill told the dispatcher.

Lauren received more texts: "Hey Bitch your car is @ Stadium Key in passenger seat on floor. This was only a favor for Sean. He never told you he is in the Military reserves like us. Good luck idiot!"

Followed by another text: "Go kill yourself."

A little before 6 p.m. on Oct. 10, Lauren retrieved her car. The dispatcher spoke to Jill again to say that it was over, that she watched on surveillance cameras as Lauren drove away.

"Thank you so much. You guys are so wonderful," Jill said. "I so much appreciate it."

No information about the Oct. 10 incident -- that Jill had asked for police help, that she had described Rowland as a sex offender, that she was afraid for Lauren's safety -- ended up in police reports.

"I didn't know none of that," says Miguel Deras, the police officer who soon would be assigned to Lauren's case.

Det. Kayla Dallof and Officer Miguel Deras were among the campus police officials who played pivotal roles in Lauren's case.

‘I GOT POLICE INVOLVED’

The next day, Oct. 11, Lauren kept getting texts from strange phone numbers.

Sean had been in an accident. He was in the hospital.

Lauren didn't know whether to believe the messages, especially one that said Rowland had died.

But then Lauren got a text from a number she knew to be Rowland's, and she saw he had recently posted on social media. The texts about an accident and the hospital had to be lies, but were the messages really from Rowland's friends, or were they from Rowland himself? Some spelled his name "Sean" and others spelled it "Shawn."

On Oct. 12, she called 911 to connect with university police. Her hesitant voice on a recording of the call reflects the nervous reluctance her friends and Jill said she had about involving police.

"I've been getting these texts from different people -- they're saying he's in the hospital and he passed away -- but I got a text from him and he seems to be alive," she told a dispatcher. "I got a text about asking if I wanted to go to a funeral -- his funeral -- and I think they're trying to lure me somewhere."

"Are you trying to avoid him?" the dispatcher asked.

Lauren paused. "I would say it's more just his friends."

Lauren told the dispatcher that she had blocked several numbers. The dispatcher said an officer would be in touch.

Another text arrived: "Shawn is gone because of you! Don't come to his funeral. We had his phone texting you. Cold Bitch."

Lauren wrote back, "Please don't contact this number. I got police involved."

"So do we," came the response.

Officer Deras was assigned to take a report from Lauren. He had been on the campus police force for three years but had not handled a case like this before.

He spoke to her by phone that day, Oct. 12, and told her what police would repeat several times: There was little they could do. No specific threat had been made against her, they said, and even she wasn't sure who had sent the messages.

Police and Lauren would later figure out that it was Rowland sending all the texts, using different numbers and harassing her without crossing a line that would trigger police action. And campus police, as a state investigation later found, had nobody trained to recognize behavior that fit a pattern of domestic abuse, someone who might recognize that the harassment could escalate.

Deras told Lauren to call back if she needed anything.

In her Oct. 13, 2018, statement to campus police, Lauren laid out the efforts to extort her, which started soon after she broke up with Rowland.

Extortion

On Saturday, Oct. 13, Lauren woke up to an email and text from an unfamiliar source. The sender said they had an explicit image of her and would release it if she didn't pay $1,000. The person later demanded another $1,000. Alex says Lauren suspected it was Rowland; Lauren knew he had images the two had taken together. But she couldn't be sure. Lauren texted Rowland, who responded by saying that he didn't know who sent the message but that he was being blackmailed, too, and would try to get to the bottom of it.

Lauren sent the $1,000 over Venmo. Then she called police to report it.

Lauren spoke with Deras by phone. She also emailed him screenshots of the threats, along with copies of the photos, writing, "People are threatening to send nude photos of my ex-boyfriend and I and blackmailing me."

Alex says Lauren became frustrated by what felt like a slow response and decided to go see Deras in person. Deras says it was his idea that she come into the station. He says that he was working his shift at the university hospital when he received the material from Lauren and that he thought the situation was "more serious" than Lauren was letting on.

Lauren and Alex arrived at the police station at 11:16 a.m., Lauren wearing a University of Utah T-shirt and carrying a bright red track and field backpack. The two women sat alone in the vestibule for 15 minutes until Deras greeted them, and they were joined later by Officer Aaron Nelson.

The officers called Lauren's bank to see whether she could recover the $1,000 she had sent by Venmo. Alex says the officers suggested it might be a common internet scam and not from Rowland at all.

And Lauren still seemed confused about who was attempting to extort her. When she called police earlier that day, she told the dispatcher, "Sean Rowland is the one messaging me." In the police report Lauren filled out in the vestibule of the station, she wrote that it could have been Rowland and that she had no way of knowing who else had seen the images.

"Anyone could have been extorting her," Deras says. "There was random phone numbers, emails from -- unknown emails from I don't know where -- that they wanted to blackmail her."

Nelson, the officer there with Deras, told ESPN he reached out to the on-call detective, Kayla Dallof, and suggested that she come in to interview Lauren, especially because Lauren might be more comfortable speaking to a woman. He says Dallof, who had been a detective for less than a year and was scheduled to be out of the office until three days later, called her supervisor, Det. Sgt. Kory Newbold, to ask whether she could come in to interview Lauren.

According to Nelson, Deras and another officer, Dallof said Newbold told her it was impossible to know whether the extortionist was someone in the state or even in the U.S.

"She said Kory didn't think it was that big of a deal and she should just talk to [Lauren] when she came into work. It wasn't something we needed to send an on-call detective for," Nelson says. "When you look at it as far as all the other cases like that, it was true. If we had more evidence that it was actually [Rowland,] it might have been different."

Newbold died of a heart attack while on duty in 2021 and was never interviewed for this story. Dallof declined to answer questions from ESPN.

Deras told Lauren that the case would be assigned to Dallof and that Dallof would be in touch on Tuesday, Oct. 16.

As Lauren filled out the report, surveillance video shows her and Alex frequently laughing. Lauren seemed relieved to have the police involved.

"I guess she felt, in a way, safer," Alex says.

As the day went on, however, Lauren's worry returned. At 5:48 p.m., she called Salt Lake City police. "I was just concerned because I wasn't sure how long [campus police] were going to take to file the arrest," Lauren told a dispatcher.

But because Salt Lake City police do not have jurisdiction over the campus, the dispatcher transferred her back to the university's 911. Lauren asked the university dispatcher when an arrest might be made. The dispatcher said she could connect her with an officer. While Lauren held, the dispatcher contacted Deras, then told Lauren that Dallof would be in touch.

Dallof had been assigned to follow up on a handful of cases, including a sexual assault allegation, and had to make several court appearances that week, according to the university.

Deras says that he asked Dallof that week whether she had spoken to Lauren and that the detective replied that she hadn't but that she was working on search warrants for Rowland's phone. He says he doesn't know what else he could have done.

"That's where I needed more experience on these types of cases, doing follow-ups. But we were trained as first-line officers to document everything and pass it over to the detective," he says. "They want the detectives to do the follow-up."

MANIPULATION TACTICS

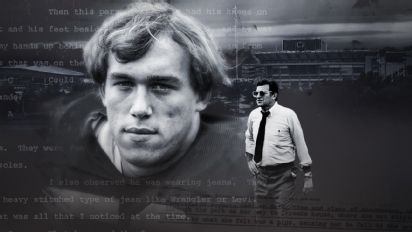

Over the course of his 37 years, Rowland showed a talent for manipulating and lying to people, even describing himself that way in many interactions with law enforcement.

He was born in New York City in 1981 and adopted when he was "young" -- a parole report was not more specific -- along with two girls, by two Belizean immigrants in their early 60s living in Brooklyn. Rowland had two older adoptive stepsiblings he never met. His stepsister, reached by ESPN, said she knew nothing about him; she was already in her 30s living in Los Angeles when he was adopted. But she added that when she considered adopting a child, her father discouraged her: "He said, 'Don't do it, don't do it. You don't know nothing about those kids.'"

In parole hearings, Rowland said his parents died when he was 15. That was true of his mother, but death records obtained by ESPN show his father died 11 years later.

Rowland spent much of his young adulthood bouncing between schools and group homes throughout the U.S. He started high school in the Bronx but graduated from a high school for troubled youth in Estes Park, Colorado, where he played a role in a school production of "Grease." He spent time in a group home in New York and a Buddhist institute in Berkeley, California.

Eventually he landed with the Job Corps in Clearfield, Utah, and worked as a certified nurse's assistant while the Job Corps paid for him to attend Salt Lake Community College. In 2003, he transferred to the University of Utah, he told parole officials.

"And that's when I got in trouble."

Rowland said he became addicted to meeting women online and arranging hookups on the weekends.

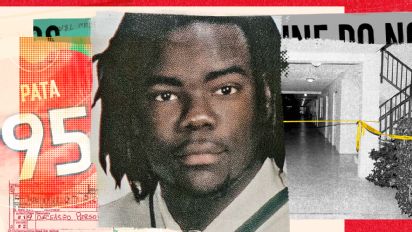

In 2003, Rowland met a 17-year-old girl online. According to a police report obtained by ESPN, Rowland went to her house while her parents were on vacation. He asked for a tour of her home, and the two ended up in her bedroom watching TV. They started kissing when Rowland told her, "Have sex with me," and, "just cooperate and don't try to run." Then he raped her. "I was so scared I put my head under my pillow and started crying," she told police. "I didn't want him to hurt me more or try to kill me."

Two days later, Rowland went to meet someone he thought was a 13-year-old girl -- with whom he said in an online chat he wanted to "have wild sex." When he arrived, he was arrested by a police officer working a sting operation.

Rowland was charged with rape and enticing a victim over the internet, but the 17-year-old rape victim proved to be a reluctant witness, says Paul Amann, the former assistant Utah attorney general who prosecuted the case.

"There was a strong likelihood that the victim in this case was not going to be able to withstand trial," Amann says. "She did testify at a preliminary hearing, and she had a very hard time."

Instead, Rowland pleaded guilty to third-degree felony attempted forcible sexual abuse, along with the "enticing a minor" charge. He was sentenced to one to 15 years in prison, with a sentencing recommendation that he spend about 3½ years of that term behind bars and the rest on parole.

He was first eligible for parole in 2005. During his hearing, he confirmed the details of the 2003 rape, and the parole board denied his request. The board told Rowland he could reapply in two years, after completing sex offender therapy.

Rowland's voice on the recording of that first parole hearing is reasonable and calm.

"He was very handsome; he's soft-spoken, well-spoken," Amann says. "Even when I was arguing for him to go to prison, I felt kind of sorry for him. He seemed to have so much going for him."

Rowland's prison record includes a handful of incidents. According to a Utah Department of Corrections report, Rowland was cited in 2006 for unauthorized computer use and "manipulating" a staff member into letting him use a computer. He also got into a fight with another inmate and "had to be physically restrained by several officers." He spent 14 days in isolation for that.

When he came up for parole again in 2008, he hadn't completed sex offender treatment, so the board postponed his hearing another two years. In October 2010, he was again denied parole, this time because he'd been kicked out of the treatment. At that point he had spent almost twice as much time in prison as had been recommended.

"Your failure to make progress consisted of what [the therapist] describes as, you were less than candid, or you manipulated and lied in treatment, you maintained a defensive stance with regard to your behavioral act," the presiding officer at his parole hearing, Dick Sullivan, said to Rowland in 2010.

Two years later, in 2012, Rowland returned to the parole board. Kim Allen, the hearing officer who handled Rowland's 2005 hearing, ran through Rowland's history -- including that he "admitted sexual attraction to teenage girls and adult women who were vulnerable," Allen said.

In that hearing, Rowland again confirmed the details of the 2003 rape. He also said he had frequently used "manipulation tactics" to get women to do what he wanted.

How many women had he raped, Allen asked.

"Similar to [the 17-year-old victim]?" Rowland asked. "Two."

Under oath, Rowland admitted to committing two other rapes for which he had not been charged.

Asked why Rowland was not referred for charges, the Board of Pardons and Parole sent ESPN a statement saying, "Although those testifying in hearings are placed under oath, there is not a Miranda warning, and the individual retains their right against self-incrimination under the Fifth Amendment. The Board is required to provide a fair and neutral decision-making process, like judges in a court of law. The Board's role is to ask questions and respond to the information provided, but it cannot be a fair venue if we are also involved in investigatory or prosecutorial actions."

During that same hearing, Allen also asked Rowland how many women he had "manipulated" into sex.

"I'd say about 50," he said.

Allen noted that Rowland had been in prison for about eight years, far more than the 3½ years he had been expected to serve. But this time, Rowland had completed sex offender therapy. He had even become a mentor in the program, a source with firsthand knowledge told ESPN.

"It would appear that we've wanted you to do something you've finally done, so maybe it's time to give you a shot at parole. And that'll be my recommendation to them," Allen said.

The board granted Rowland parole, and he was released from prison in 2012.

Because he had been convicted of enticing a minor, Rowland was classified as a Group A offender. As such, he was not allowed to have contact with minors, use social media, or use alcohol or drugs, and as a felon, he was prohibited from having a gun. So when his parole officer went through his phone six weeks after his release and found accounts with Facebook and MeetMe, Rowland was sent back to the parole board for a violation hearing.

"You weren't out very long and went right to that," hearing officer Cathy Crawford said with an exasperated sigh. "That's a concern."

Rowland landed back in prison.

In 2013, he was paroled again. He began dating a woman who worked at the University of Utah, and she got pregnant. They had a son. (She did not respond to numerous requests for comment from ESPN.) He also had run-ins with law enforcement at least twice, none of which resulted in his returning to prison.

On Oct. 31, 2015, Rowland rear-ended a car. A man stopped to see if he was all right, and Rowland "entered the passenger seat of the good Samaritan's car, telling him he needed to get out of there." The driver, who told police he cooperated because he was intimidated by Rowland's size and "aggressive nature," dropped Rowland off near his home. Rowland eventually admitted to his parole officer that he had been involved in a hit-and-run.

His parole officer wanted Rowland arrested for kidnapping, fraud, damage of private property and leaving the scene of an accident. But the board decided that, although Rowland's behavior was troubling, a warrant wouldn't be justified unless he was criminally charged. The man declined to press charges, and Rowland remained free.

Rowland met a 20-year-old woman, Kara Strople, through a dating app in late 2015, she recalls. "He just seemed very normal and easy to talk to," she says.

They went out a few times "casually," she says. But then his behavior changed. He would text her incessantly and pressure her for sex. When she declined, he shifted gears and said, "Let's just be friends," which she says was disarming. But then he started to pressure her again.

Strople says she "politely ghosted" Rowland and thought she was finished with him.

Weeks later, on a Saturday morning, she woke up and looked at her phone. She had dozens of missed phone calls and texts from him. "And the very last one was, 'Hey, I left some piece of luggage and a backpack outside of your door, call me or text me or something and I'll explain.'"

He asked her to meet for brunch to explain.

At a restaurant, Rowland unloaded about how his parole officer had surprised him the night before -- "I'm like, 'You have a parole officer?'" -- and that he worried the officer would discover he had two phones. One had material that would violate his parole conditions. He told Strople that when his officer wasn't paying attention during the visit, Rowland had thrown his second phone under his stove and fled. He was now wanted by authorities.

When she asked why he was on parole, he said he'd had consensual sex with a 17-year-old but didn't know she was underage. He cried and said he couldn't go back to prison and wanted to get a bus ticket to go to New York. She says she urged him to turn himself in. Eventually, he did.

Strople's account matches Adult Probation and Parole records of that time period: On Feb. 11, 2016, two parole agents checked on Rowland. While they inspected his phone and searched his home, Rowland fled, and the officers issued an arrest warrant. "Rowland made it very clear he was not going to do parole anymore. He stated he would act very aggressive if another [parole officer] came to his house again," one of the officers wrote in a report.

Rowland was hit with multiple violations: fleeing an officer, using online social networks without approval and possessing pornographic material in violation of his parole, and skipping his sex offender group therapy. Rowland later told a parole board hearing officer that he didn't mean the threat to his parole agent and that he was only frustrated. The parole board recommended Rowland return to prison for the remaining three-plus years of his original 15-year sentence. He had to reenter sex offender therapy but could apply for parole again after he finished.

Rowland called and wrote to Strople repeatedly from prison -- she gave ESPN letters she still had -- and alternated between praising her friendship and berating her for not doing enough to help him. He asked for favors such as canceling his gym membership and online accounts. He also wanted her to help his landlord clean out his apartment. He told her she could keep his television as compensation.

At Rowland's abandoned apartment, she looked under the stove and found a black Nokia phone that wasn't password protected.

"I opened it up and saw a whole bunch of really sleazy shit. Like messaging every single woman he could find on [dating apps]," she says.

Rowland told Strople he wanted the phone back. He said he would send friends to get it.

Strople says he got more aggressive, insisting that she owed him $1,000 and telling her at one point that "karma is a bitch." She took that as a threat but continued to engage with him because she was afraid he might have a friend harm her.

And when Rowland got out, "I did think that he was just going to show up at my door, and I didn't think that he would be nonviolent."

He became parole-eligible again in January 2018. The board faced a choice: Monitor Rowland through 13 months of parole or keep him locked up and then let him go, free of supervision.

In its statement to ESPN, the board said, "In many instances, public safety is better served with some amount of community supervision rather than an unconditional prison release."

On April 17, 2018, as Lauren was in the second semester of her junior year, Rowland walked free on parole for the third time.

Megan Thomson, the parole agent assigned to him, estimates she had about 70 to 80 cases at the time. She says Rowland was considered "low supervision," based on his record and scoring assessments. According to state records, Rowland was considered a "moderate" risk to re-offend. His therapist said "he was doing really well," Thomson says.

Still, Thomson always had another agent with her when she went to visit him, per protocol. Rowland acted as though Thomson intimidated him, she says, but she thought it was an act to disarm her.

"It seemed like he was just kind of going through the motions," she says. "Jumping around jobs, not trying to get himself established with one thing. ... He was canceling a lot, his sessions or his appointments with me and with therapy, he would sometimes no-show. He would not finish his homework for therapy."

In late May 2018, Thomson scrolled through Rowland's phone and saw messages with women he wanted to date. He told Thomson he met the women through a dating app but didn't consider that social media.

"I told him I'm considering as a social media site which is against his parole conditions," she wrote in her report. "He didn't like my response but said he will comply."

In August, Rowland tested positive for marijuana after confessing he had smoked it. He said he was in pain from a thrombotic hemorrhoid that had required surgery. "I came down on him and told him to get his crap together," Thomson wrote in her report.

Amann, the former assistant Utah attorney general who prosecuted Rowland in 2003, says marijuana usage should have been reported as a parole violation with the intent of sending him back to prison. But Thomson insists she could never have gotten a warrant for his arrest based on that. If Rowland had a history of substance abuse, she says, it would have been a different matter.

A spokesperson for the state Department of Corrections says Thomson is correct. "The type of violations [Adult Probation and Parole] was aware of during Rowland's parole would not have typically returned someone to prison," Kaitlin Felsted, the communications director for the corrections department, said in a statement.

On Sept. 8, a 24-year-old woman, Sarah Emily Lady, walked into a Salt Lake City gun store with Nathan Daniel Vogel, 22. She purchased a .40-caliber Beretta and then gave it to Vogel. He would later tell police he'd been afraid his military background would cause a delay in the purchase, so he asked Lady to buy it for him. A short time later, Vogel -- who had been a bouncer at the bar where Rowland met Lauren -- lent the gun to Rowland. After Lauren's death, Vogel would plead guilty to a federal gun charge, saying that he had owed Rowland $200 and that Rowland had "manipulated" him to get the pistol. Neither Vogel nor Lady returned messages from ESPN.

On Sept. 30, a month after Rowland and Lauren started dating, his therapist wrote a report for his parole file. It reads, in part, "He reports that he is trying to stay single at the present time and has gone on a couple of dates, but is not wanting a long-term romantic relationship."

UNAWARE

By the day Lauren visited the police station with her friend Alex, Saturday, Oct. 13, 2018, Lauren and her mother Jill had contacted University of Utah Police at least three times.

They had alerted police that Rowland was a convicted sex offender, and that Lauren had received harassing messages and been extorted. Only once did someone run his name through O-Track, Utah's database that tracks offenders.

The dispatcher who performed a check that day had been on the job for a month and was still in training. She had never used O-Track. She'd later tell state investigators that her supervisor and an officer were present when she checked but that she didn't click a tab that would have displayed Rowland's parole status.

The school's internal investigation later found that no University of Utah police officer had ever checked someone's corrections status and that no one knew how.

The state later identified another flaw: Nobody received notification when an O-Track status check was done unless that person was being cited or charged. Thomson, Rowland's parole agent, had no way of knowing campus police were looking up his record. Rowland's name, along with 177,382 other names that were checked during his 188 days on parole, sat in a database that wasn't regularly monitored.

So the University of Utah police had no idea Rowland was on parole, and his parole officer had no idea school police were looking into him. Extorting someone for $1,000, which Lauren had already paid, was a Class A misdemeanor and would be a violation of his parole terms. The request for another $1,000 would have elevated the crime to a third-degree felony, meaning Rowland could have received an additional sentence that lasted well beyond the May 2019 expiration date of his original sentence, long after Lauren was to graduate from the University of Utah.

No one from the campus police, including Deras and Dallof, checked Rowland's O-Track status again, a state investigation found. No supervisor checked whether they had done so or said they should.

What's more, police officers' failure to check Rowland's parole status was more than an oversight. It was unwritten policy. University Police Chief Dale Brophy told officials he "had been burned" by Utah's Adult Probation and Parole when he was still an officer with West Valley police. Several knowledgeable sources told ESPN that Brophy feared the AP&P might jeopardize ongoing investigations.

"Standard police training would call for an officer to contact AP&P while checking potential suspects' backgrounds in the course of an investigation," the university said in a statement to ESPN. "We suggest reaching out to former Chief Dale Brophy to ask about department protocols and policies regarding AP&P."

Brophy declined multiple interview requests from ESPN and didn't answer questions sent via email.

‘HE WAS AFRAID’

On Oct. 16, six days before he killed Lauren, Rowland went to his job at a call center run by General Dynamics Information Technology with the intention to quit.

He told his supervisors why.

According to an audio recording of an interview that campus police conducted with one of Rowland's supervisors three days after Lauren's death, Rowland told the supervisor that he had extorted his ex-girlfriend. ESPN obtained a recording of the supervisor's interview.

"He just told me ... he had sent her messages from another phone telling her that he wanted money so that he wouldn't release [the photos]. ... $1,000 is what he said she sent him," the unidentified supervisor told police.

"He said that he had access to her email on his phone because she had logged into her email from his phone before, and he said that he could see that she sent messages to the campus police of screenshots of the conversation, and so he knew that she had contacted authorities about it."

"And so he said he was afraid. He didn't want to go back to jail. And he knew he couldn't run forever."

Rowland opened a browser on his phone to show a co-worker the statutes he believed he violated, the supervisor told police. He even used a co-worker's phone number to set up Venmo for the initial payment. He initially wanted to resign but later changed his mind and told the supervisor he would rather take a leave of absence, and the supervisor agreed.

Rowland's confession to co-workers was clear probable cause to detain him, law enforcement experts say. No one from the company called the police or Adult Probation and Parole.

ESPN played the recording of the police interview for Thomson, Rowland's parole officer. "I'm pissed," she said. "That's just another thing that could have been brought to my attention." Had a General Dynamics employee alerted AP&P, Thomson says, "I would put him in handcuffs, and take him to my office and interview him." By law, she could have kept him for 72 hours, which might have given police enough time to establish that he was the one who had extorted Lauren.

"That," Thomson says, "could have changed everything."

General Dynamics, which was in the process of selling the call center when Lauren was killed, declined comment to ESPN. School officials declined to release the names of company employees who were interviewed.

Thomson suspects the extortion was Rowland's motive for killing Lauren. She had not only jilted him, "she was also a threat. She was the one that would be sending him back to prison," Thomson says.

Rowland also was scheduled to take a polygraph test on Nov. 2 as part of his parole supervision, where he would have been asked whether he had followed his parole conditions or committed new crimes.

"To this day, even though I know I did everything I possibly could, I still feel accountable," Thomson says. "I still feel, if I could have done something differently ..."

Lauren turned to campus police, including officer Miguel Deras, when Rowland texted her to say that he knew "everything" and asked why she had contacted authorities.

‘I KNOW EVERYTHING’

Two days after Rowland confessed to his supervisor, Lauren sent Deras an email filled with messages from Rowland -- asking if he could pick up stuff he'd left in her room, asking if they could meet -- and a photo of himself.

By that time, housing supervisor Diamond Jackson had learned Rowland was a sex offender and again alerted her supervisors that he was harassing Lauren. Again, she says, she was told that officials couldn't infringe on Lauren's privacy. Jackson says that she didn't like it but that it "made sense" because it was consistent with school policy.

On Friday, Oct. 19, Lauren was on the phone with her friend Alex when she received a text from a number she didn't recognize: "I know everything. Why did you go to the police?"

That prompted Lauren to call Salt Lake City 911 a second time. As Lauren, sounding distressed, started to explain her situation, the dispatcher asked whether she had spoken to campus police. Yes, Lauren said, but "they haven't updated or done anything." The dispatcher asked why Lauren called city police.

"Well, I thought it was weird that there are people who know about the entire case and the harasser seemed to know more about it, more than me, and I'm concerned there might be an insider who's letting them know about the case," she said. "Because I haven't gotten updates and it's been a week."

The dispatcher said to call campus police again and ask for her detective, or maybe the detective's supervisor.

When Lauren called campus police, Deras said he would reach out to Dallof.

Alex says she was with Lauren when Dallof called that evening and apologized for not being in touch sooner. Dallof asked basic questions she should have already known by this point, Alex says. The detective told Lauren she was off work but due to return four days later.

Oct. 22, 2018, started with a crisp chill in Salt Lake City, the temperature in the high 40s. Haze hung over the valley most of the day.

At 6:22 a.m., Rowland parked his neighbor's silver Buick outside Lauren's dorm. He walked around on the grass outside her window before disappearing from surveillance footage.

A little after 9 a.m., she left her dorm for a short walk to the Heritage Center student services building for breakfast. At 9:57, Alex got a call from her saying she had received a text from deputy campus police chief Rick McLenon, asking her to come down to the department. But the text was filled with typos and misspellings. McLenon's name was even spelled "Mclenon."

"She was very concerned and scared. 'What do I do? Like, is this real? I don't know.'" Alex says. Lauren called Deras at 10 a.m. The call lasted less than a minute.

She left the Heritage Center a few minutes after that for an 11 a.m. appointment with a therapist at the student counseling center. While Lauren was there, Rowland roamed the Heritage Center, then walked back toward her dorm.

Lauren called Deras again at 11:55 a.m., then twice more in the following 20 minutes.

Lauren and Deras then met in person at the main student union -- Deras says they realized they were both there -- and she showed him the text claiming to be from McLenon. Deras says he told her that it was not McLenon's number and that she should forward the message to Dallof.

According to a state investigation, Deras didn't tell his supervisors about the meeting with Lauren or the text claiming to be from McLenon. He says now that he should have. No mention of the meeting appears in the official university report, although Deras contends he told Newbold and McLenon about the meeting a week after Lauren's death. He also says he later told internal affairs investigators, which his attorney, J.C. Jensen, backed up.

Lauren emailed Dallof about the text, saying she thought she was being lured. Dallof, who was still off work, wouldn't see the email until it was too late.

Rowland appeared at Lauren's dorm again at 1:34 p.m. Surveillance video shows a young man letting him in the locked door. Rowland walked around inside and left. At 2:25 p.m., he returned and the same man let him in. At 4 p.m., Rowland was in the building again, repeatedly checking the entrances.

At 4:56 p.m., Lauren bought something to eat at the Gardner Commons Food Court, where she ate and studied for the next 50 minutes. Around that time -- and for the next three hours -- Rowland was walking in and around her building. The same young man let him back into the building two more times. He would later tell police that Rowland hung out in his dorm room that evening and that Rowland showed him the gun he carried around campus that day.

At 7:59 p.m., as she walked from Gardner Commons to her apartment, Lauren called her mom. Jill and Matt were working out in adjacent basement rooms in Pullman. Jill put the call on speaker.

"I could hear their conversation. It was very lively, very happy. Lauren was looking forward to things," Matt says. "Ordinarily, I would tell Jill to please turn it down, but ... she was so happy."

At 8:16 p.m., while she was still on the phone with her mom, Lauren walked through the parking lot just west of her building. Rowland was between the cars, his hood up, holding a phone to his ear. He turned so as not to be recognized. Lauren walked by. He began to follow her. She did not notice.

"All of a sudden, I hear her yell, 'No, no, no!'" Jill says. "And then I sort of hear her being dragged away and her phone fell."

Then Jill and Matt heard nothing.

Matt called 911 in Pullman, which connected him to campus security within two minutes. His voice was calm and patient. He described what he had heard, that she had recently broken up with someone, that campus police had been involved.

The dispatcher left the line to consult with an officer. While Matt waited, Jill said something to him. Matt responded, still icy calm, "I know. We've got to concentrate on helping."

The dispatcher returned, and Matt gave the ex-boyfriend's name: "Sean Fields." He explained that Lauren's phone was not dead, that she must have dropped it and the connection was still open.

As they talked, a woman's voice came over Lauren's phone, asking whether anyone was there. Matt said, "Hello?"

"Hi," the woman said. "I have a backpack and ID and a phone..."

Matt interrupted. "OK, OK. Can you just stay there? I think she was mugged."

"Is she OK?" the woman said. "I was about to call the cops."

They decided she should call 911 directly. The woman explained to police where she was. The McCluskeys then hung up with police and waited. For the next 85 minutes, they heard nothing.

Jill frantically called Lauren's friend Regina Snider. Lauren might have been kidnapped. Was there anything Snider knew that might help? Snider thought of the photos she had taken with her phone two weeks earlier at a restaurant with Lauren, of the criminal who looked like Lauren's boyfriend. She forwarded them to Jill.

Around 9 p.m., campus police summoned everyone scheduled to work the overnight shift. Officers were given the name "Lauren McCluskey" as well as Rowland's. Someone said over the radio that they thought there was an open case involving Lauren's name. Dallof, among those called in, checked her email from the scene and saw the message Lauren had sent earlier.

At that point, police believed they were investigating a kidnapping. Word went out to look for a silver Buick. Around 9:55 p.m., someone spotted one in the parking lot. Lauren's green Jeep was next to it. There was a shell casing between the cars. An officer looked in the Buick. There was a woman in the back seat.

The officer, who spoke to ESPN on the condition his name not be used, opened the passenger door and saw Lauren, her head against the driver's side of the car. Six more shell casings were on the floor. It looked as if she had been shoved into the car and shot multiple times. The officer checked her neck for a pulse. There was none.

"I don't think she would have survived, but we were on scene for over an hour before her body was discovered," the officer said. "Which gave him more than an hour ahead of us."

Around 10 p.m., Lauren's track coach, Kyle Kepler, called the McCluskeys.

"He told me that they found her, and I said, 'Is she OK?' And he said, 'I'm sorry, she's not. She's gone,'" Jill says. "And I ... that was when I just started crying and Matt knew what he had said by my response."

Matt says hearing the news was "like getting hit by a baseball bat. ... It was that physical."

Confirmation came more slowly for Lauren's friends. Diamond Jackson was in a housing staff meeting when the school sent out an alert that someone had been shot. "I remember walking across the dining hall and looking at one of the giant TVs and looking to my side and I see his face: That's his mug shot," she says. "I just stared at him like, 'It's him.'"

She tried calling Lauren and got no answer. She called Alex to say the victim on the news had to be Lauren. "Everyone's trying to call Lauren, and no one's able to get in contact with Lauren," Jackson says.

Alex prayed it wasn't Lauren. She said her father called at 5 a.m. She said she didn't want to know. And he said, "You need to know because you're going to hear about it."

"And so he told me."

Snider got a text from Jill: "We lost her."

According to police, a short time after killing Lauren, Rowland called a woman he had met online a few nights earlier. He asked her to pick him up at a light-rail station at the school. They went to dinner downtown, then walked around the state Capitol building. They went back to her apartment, where he showered. She then dropped him off at a coffee shop. A short time later, she saw his face on TV and called the police.

At 12:56 a.m., a Salt Lake City police officer saw a man matching Rowland's description near downtown, about 4 miles west of campus. Police pursued him on foot. Rowland broke through the back door of the Trinity AME Church, a schoolhouse-sized red brick building with a single spire that is a landmark for the city's small Black community. As police entered, they heard a shot. A .40-caliber Beretta was found next to Rowland's body.

Trinity's associate pastor, Daniel Stalling, later said no one at the church had ever seen Rowland before.

THE RECKONING

When Matt McCluskey reflects on the hours and days after Lauren's death, he's sometimes stunned by his calm initial reaction.

The tone of his voice on 911 calls is that of someone reporting a cat stuck in a tree. Maybe it was the scientist in him, or the former naval reserve officer. There were tasks to be done. Help the police. Wait for the call. Then, later, how to tell their son, Ryan, a student at the University of Washington in Seattle.

"I actually did sleep for a couple of hours. It was almost like, well, I have to be ready for what's coming next. I didn't cry. I was totally shocked," Matt says. "And I just said, 'OK, we just have to really focus on the next task.'"

He caught a 5 a.m. flight to Seattle and called Ryan from the airport to be sure his son didn't hear the awful news somewhere else first. It wasn't until Matt got back on a plane to Pullman that afternoon, when there was no next task, that he finally broke down.

Matt and Jill then turned to all the wretched obligations that come after someone dies: arranging a funeral, seeing Lauren's body, receiving mourners. Burying their daughter.

Then, the eating, sleeping, dressing, brushing teeth, doing dishes. Always the next task.

And then came the work of figuring out what happened during the seven weeks leading up to her death. There were also trolls.

LAUREN'S MOTHER, JILL McCLUSKEY

In the days after Lauren's murder, there was some chatter on the internet, what Matt called "garden-variety racism" -- people saying that Lauren deserved to die or that it should have been obvious to her that Rowland was a threat because he was Black. Matt says the ugly comments were just a distraction.

"It's just like a little cockroach that crawls on you," he says.

The more important issue when it came to race, the McCluskeys say, is that if Lauren had not been white, her story might never have gotten the attention it did.

"There are girls who are as precious to their parents as our daughter is to us, and they do not receive this level of attention. I think people should really think about that. I certainly do," Matt says. "There are reasons, some good, some maybe not so good, why Lauren made international news. But we should always remember that there are lots of Laurens out there who you don't hear about."

Fifty-eight days after Lauren was killed, then-University of Utah President Ruth Watkins held a news conference to discuss the school's just-completed investigation. The facts about campus police and housing were damning. The report detailed recommendations for both departments, including better communication, more officers and better training.

But no one from housing or the police was fired or disciplined, and Watkins summed up the investigation with words that would haunt nearly everyone involved.

"The report does not offer any reason to believe this tragedy could have been prevented," Watkins said.

Jill says the statement made her "physically ill." Her attempts to reach Watkins went unanswered.

That was it for the McCluskeys. Up to that point, they wanted only an apology and some signal that the school was moving to ensure the events leading to Lauren's death could not happen again.

The McCluskeys filed a $56 million federal civil rights lawsuit against the university. They say their goal was to get a settlement large enough that insurance companies would force other universities to strengthen campus safety.

"I just thought, how can you get any better if you don't have any consequences to horrible mistakes that ended in a death?" Jill says.

Watkins, who left the school at the end of the 2021 spring semester, did not respond to several requests for comment.

Statements by other campus officials -- in response to the lawsuit, the school said its police aren't responsible for protecting students from off-campus individuals -- continued to cause blowback. About 100 students staged a walkout to protest what they called police indifference.

It wasn't until August 2020 that fallout hit campus police. The state launched an investigation into an allegation, first reported by The Salt Lake Tribune, that Deras had "shown off" explicit photos of Lauren to other officers.

According to a subsequent state investigation, multiple officers said under oath that Deras showed the explicit photos for "non-law enforcement reasons." Two officers told DPS investigators that Deras made an unprofessional comment about the photos, and other officers admitted to making similar comments.

Deras denies the accusations. "I would never do that," he tells ESPN in his only public comments about the case. He had left campus police to become an officer in Logan, Utah, when the Tribune's story came out, but was fired as a result of the state investigation. The incident led to a suspension for deputy chief McLenon, who later resigned. McLenon did not respond to ESPN's interview requests.

The Utah Peace Officers Standards and Training division investigated the incident but took no disciplinary action against Deras or other officers.

Eventually, the school and the McCluskeys settled for $13.5 million. Watkins apologized on behalf of the university. All the money, the family says, is going into the Lauren McCluskey Foundation, which works to raise awareness about campus safety around the world.

Since the settlement, the school has coordinated with the McCluskeys to create an indoor track facility dedicated to Lauren. The school also announced that the Center for Violence Prevention was being renamed the McCluskey Center for Violence Prevention.

Nearly the entire campus police force has been replaced since Lauren's death.

And, according to The Salt Lake Tribune, interim police chief Jason Hinojosa last fall cited Lauren's death in prohibiting his department from saying any of the following to people who report crime: "There is nothing we can do," "Why did you wait to report this crime?" and "What do you want me to do?"

There is one lingering issue for the McCluskeys: obtaining Lauren's counseling records from the university. A state records committee decided in June 2020 that the documents should be turned over, but a state law was passed the next year that keeps the records of deceased students sealed. Just this March, Jill said in a speech at the university that school counselors should receive the same scrutiny as any other campus office.

Nearly four years after Lauren's death, the McCluskeys say they are bolstered to know how many people are affected by her story, and they are working to raise awareness of campus safety issues.

‘AT LEAST EVERY HOUR’

In 2022, as the fourth anniversary of Lauren's death approaches, Matt and Jill meet two reporters at a hotel in Moscow, Idaho, a short drive from Pullman. They're here to learn some details of ESPN's investigation for the first time, and have said they'll be comfortable watching video from some of the people involved, including Miguel Deras, to offer their reactions.

They enter the hotel suite that's been reserved for the interview smiling and a little rushed from running around. There's a camera crew setting up around them, but they're used to the drill by now. This is their fifth interview just with ESPN.

Years earlier, Matt was asked how often he still thought of Lauren.

"Every second of every day," he said then.

Was that still the case, he's asked? He smiles.

"Not every second," he says. "But at least every hour."

From the outside, the McCluskeys' lives look fairly normal. They are both successful in their fields. Matt helped invent a laser microscope, and his company, Klar, is taking off. Their son, Lauren's younger brother Ryan, graduated from the University of Washington, and they rejoice in his accomplishments. They ski and hike, and in company they are quick to laugh.

They speak about Lauren often and openly, but often they find themselves encountering someone who expresses grief or condolences over Lauren for the first time, sometimes as if seeking a benediction. Jill and Matt smile warmly during those moments, and they say "thank you." Even if there is nothing new to say, they are bolstered to know how many people are affected by Lauren's story.

They sit behind a round, white kitchen table, Jill in a navy blue sweater and Matt in a green polo, ready to watch an iPad propped before them.

When the camera crew is ready and it's time to start the interview, they each take a bit of a breath. Jill sits upright, looks down and folds her hands in her lap. She has done this in every interview for four years. Jill will remain studiously composed. Matt often has a slight, understanding smile on his face.

They watch Deras deny that he ever shared or commented on Lauren's photos. They hear his explanation that he did as much as he could, but that he wasn't properly trained and the detective was responsible for case work, not him. They hear his apology.

Matt listens, then sighs and shrugs. "I don't know," he says before letting out a small nervous laugh. "I guess I just don't really care about him. I'm skeptical."

Jill nods. "Yeah. I am, too. I hope he's sincere in his apology. We can't dwell on what other people have done all the time because that would just be bad for us. So, I hope he does better in the future."

Matt considers Jill's words.

"I mean, if it really, primarily was inexperience, then that's better than the alternative," he says. "I agree with Jill that we don't spend a lot of time thinking negative thoughts about all the people in this whole mess. We don't wish ill on anyone."

They watch a video clip where Megan Thomson, Rowland's last parole agent, explains the limitations of her job, and how sorry she was that she didn't save Lauren.

They find it persuasive, and Matt says, "It sounds to me like there's really nothing she could have done." They make a point to wish her well.

They hear Thomson say how sorry she is for their suffering, something they've heard countless times. They're transfixed on video of Thomson saying, "I can't imagine just ... the amount of pain. No matter how many lawsuits or how many things that are found out or faults or anything, it doesn't take away what happened, and what they lost."

There's a long pause, and now there's no light smile on Matt's face.

"Well," he says, "she's right."

If you need help because of domestic violence or abuse, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE), text "START" to 88788 or visit www.TheHotline.org

Additional reporting and research by William Weinbaum and John Mastroberardino. Edited by Laura Purtell, Mike Drago and Jena Janovy. Video producing by Rayna Banks. Copy editing by Susan Banning and Kathryn Sherer Brunetto.

Produced by ESPN Creative Studio: Michelle Bashaw, Rob Booth, Heather Donahue, Karen Frank, Jarret Gabel, Luke Knox, Daniel Pellegrino, Garrett Siegel and Rachel Weiss.

Photos and videos from ABC News, Associated Press, Dean Hare/Daily News, KTVX/ABC4, Logan City Police Department, Pac-12, Sarah Nathan, The McCluskey Family, The Salt Lake Tribune, The University of Utah, The University of Utah Police, Utah Department of Corrections and Utah Transit Authority.